What is Lacquer?

Lacquerwares, objects coated in a hard, lustrous resin, have been made throughout Asia for centuries. An ancient art form, lacquer fragments have been unearthed at archeological sites in China dating to 5000 BC. Often taking months or years to create, lacquer can be painted, carved, molded, and set with precious metals and mother-of-pearl.

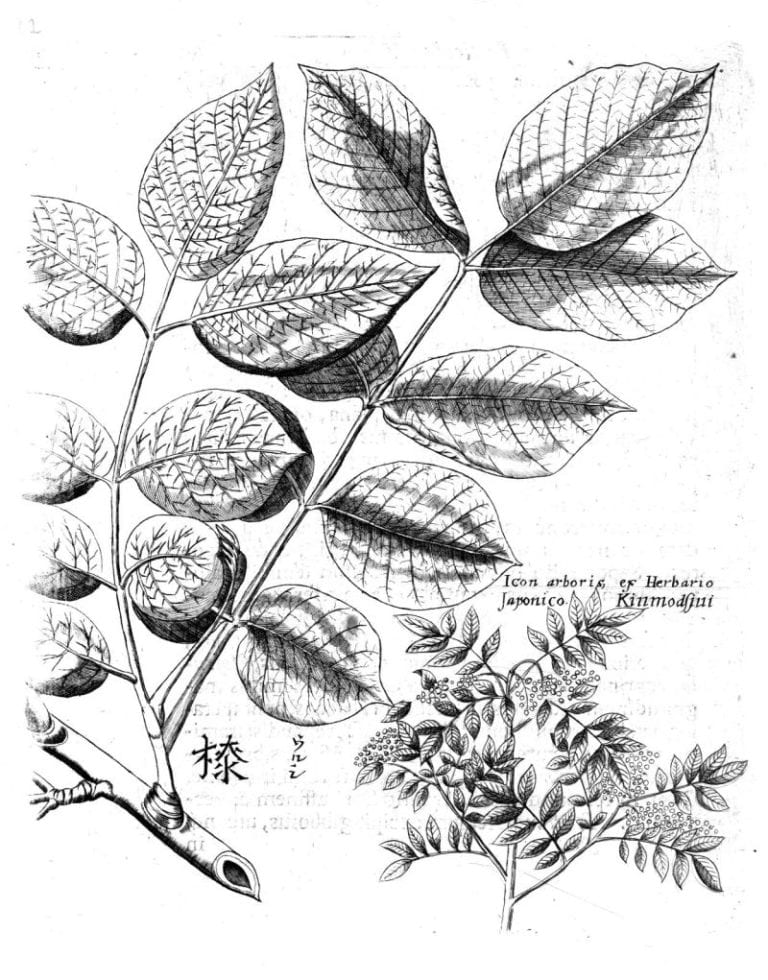

Engraving of the lacquer-producing sumac species Toxicodendron vernicifluum, From Engelbert Kaempfer, Amoenitatum exoticarum politico-physico-medicarum fasciculi V quibuscontenentur relations (Lemgo, Germany, 1712)

Lacquer is made from sap secreted through ducts in the bark of sumac trees belonging to the Anacardiaceae family of plants, including Toxicodendron vernicifluum, Toxicodendron succedanea, Melanorrhoea usitata, and M. laccifera. One component of lacquer, the powerful skin irritant urushiol, is the active agent in the sap of poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac, also a species in the Anacardiaceae family. Most lacquer workers take years to build up a tolerance to urushiol.

Applied wet, lacquer hardens when exposed to humid air. The resin molecules absorb oxygen and bond together (called polymerization), forming a hard, durable coating impervious to water, salts, acids, and alkalis. Despite the presence of the resin urushiol in most lacquerwares, fully cured lacquer is non-toxic and safe to handle.

How was Chinese lacquer made?

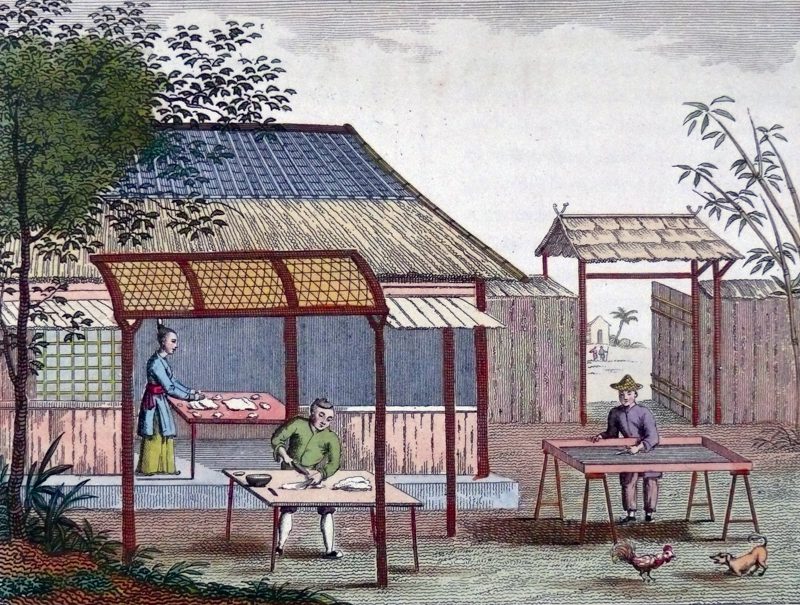

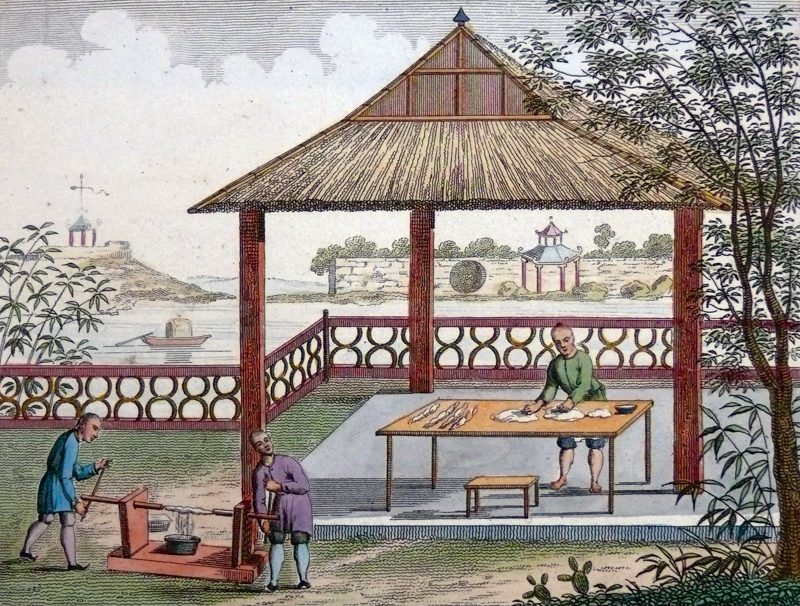

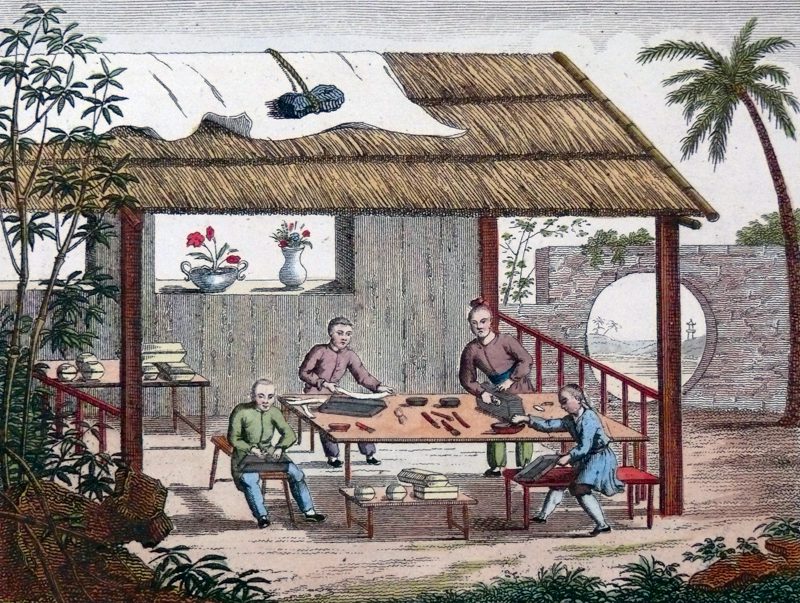

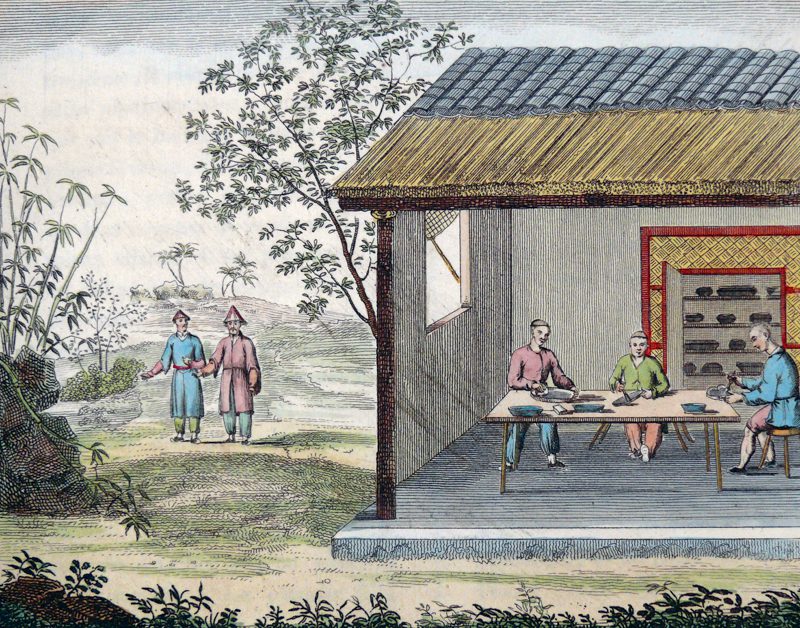

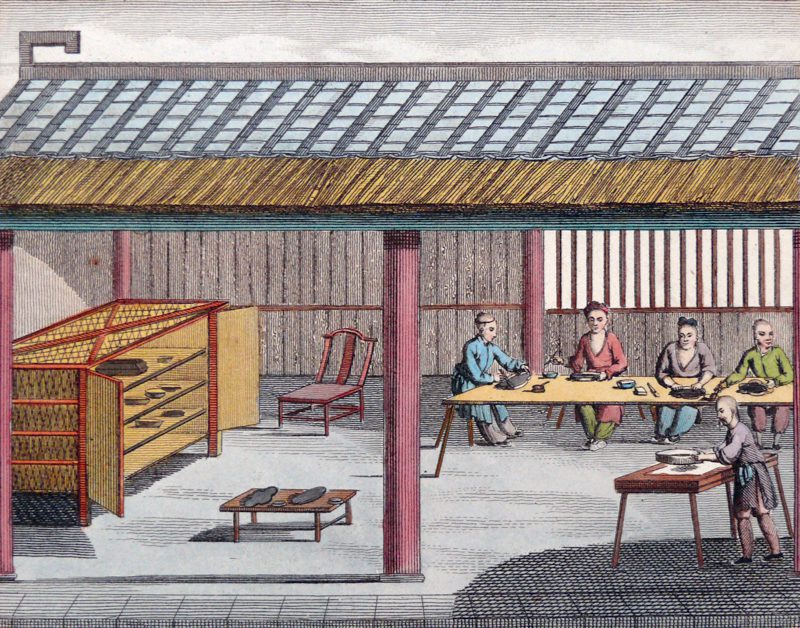

In 1740 French Jesuit missionary Pierre Nicolas Le Chéron d’Incarville was appointed to a post in China. During his seventeen years there (he died in Beijing in 1757), he befriended the emperor, learned Chinese, and studied the country’s plants and plant-based crafts, including lacquer and papermaking. His description of the traditional materials and techniques of lacquer made for domestic consumption, Art du Vernis (Art of Lacquer), was published in Arts Métiers et Cultures de la Chine (1814). The engravings reproduced here are from that work.

Traditional Chinese lacquer vs. Chinese export lacquer

Chinese producers cut corners on both the materials and time-consuming methods of making lacquerware in order to meet European traders’ demand for goods that could be ready for shipment in weeks rather than the many months needed for traditional lacquer. Their modifications, described in the adjacent display, resulted in lower-quality wares prone to long-term degradation as they aged.

Materials and methods of traditional Chinese lacquer

Gathering Sap

Between early summer and fall, lacquer workers tap mature sumac trees by slashing the bark with inverted V-shape grooves and attaching sap pans at the lowest point of each groove to catch the milky-gray substance.

Rendering Lacquer

A worker spreads the sap in a tray (front left) and exposes it to the sun for two to three hours, stirring it to hasten the processes of oxidation and evaporation needed to darken and thicken it. Depending on how the lacquer is to be used, colorants, drying agents, and additives such as pork gall, roman vitriol (cupric sulfate), and tea oil and arsenic, are mixed with the lacquer to improve its color, handling properties, and finish. Note the worker (far right) who is stirring everything in a large iron spoon, over heat, in the shed.

Removing Impurities

A worker spreads the lacquer on cotton fibers and cloth mesh, readying it for straining. The woman in the shed (rear left) is preparing the cotton batting. The man in the yard (front left) is pouring the lacquer onto the batting and preparing to roll it up for the next step in the refining process.

Straining the Lacquer

A worker (left front) wrings out a roll of lacquer-saturated cotton batting, straining bits of bark, twigs, and other contaminants, and catching the lacquer in a pot. This lacquer is further strained through silk fiber batts, which are being prepared by the man at a table in the pavilion (right rear).

Preparing the Work Piece

The lacquer is brushed onto a core, often made of wood, and workers seal the surface of the core by applying strips of cloth or paper to cover joints and imperfections.

Layering the Lacquer

To prevent the polymerized surface of lacquer from trapping unpolymerized resin below, workers apply thin coats of lacquer in as many as twenty or more layers, hardening each in a specially designed cupboard (rear right, behind the work table). To smooth the surface and prepare it for the next coat, they wet the piece and rub it with a pumice stone or soft clay brick (worker at the table, left). They apply final coats of refined lacquer with fine brushes, leaving no brush marks.

Dust—The Enemy of Lacquer

Clean equipment and a dust-free environment are essential to lacquer production. If dust is allowed to settle on wet lacquer, it can ruin a surface. Workers use special cupboards (left) to ensure a humid, dust-free environment in which to cure the lacquer.

Grinding and Polishing

After the lacquer is completely cured and dry, workers polish the top layers with pumice stones and charcoal dust, achieving a final gloss with finely ground powder suspended in oil.

Decoration

To decorate a piece of lacquerware, an artist draws a design on paper, pierces holes along the outline, positions it on the surface of the piece, and applies powder through the holes. After reinforcing and further elaborating the design with red lacquer, the artist sifts gold powder (and a combination of gold and silver powders for paler hues) onto the design before the red lacquer has completely hardened. He then adds finer details with “shell gold” (gold powder mixed with gum arabic).

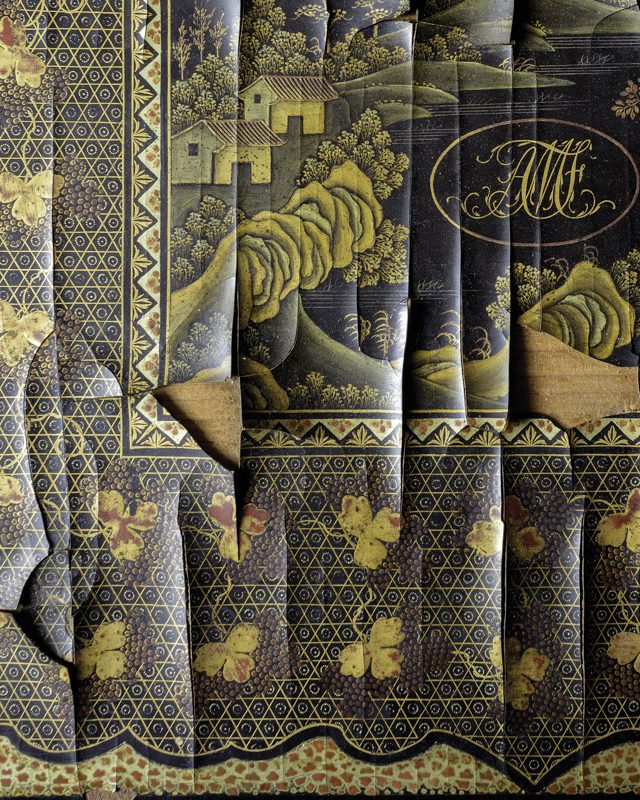

Chinese Export Lacquer before Conservation Treatment

Detail of sewing box

China; ca. 1800

Lacquer on wood, brass, ivory

Winterthur-University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation study collection

Donated to the Winterthur-University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation for study and teaching purposes, this unconserved sewing box provides an opportunity to understand the materials used in Chinese export lacquer and the processes of age-related degradation.

Acquiring Chinese export lacquer

Upon reaching China, a Western vessel’s “supercargo”—the person responsible for selling the cargo and buying merchandise for the return voyage—negotiated for the delivery of lacquerware within a span of just weeks, in time for his vessel’s scheduled return trip. To meet this demand, lacquer workers modified the materials and time-consuming methods used to produce traditional lacquer, allowing them to expand their production. These modifications, however, adversely affected the quality of lacquer made for export, as can be seen on the sewing box.

Wooden core

Cores made from improperly seasoned wood, as on the box, were prone to splitting along the grain.

Ground layers

An initial lacquer sealant was omitted from the wooden core of this box, and a protein-based binder (possibly animal hide glue) was used in place of lacquer in the ground coats, resulting in poor adhesion to the core and upper lacquer layers—notice the grainy brown ground coats on the underside of the partially delaminated, lifted sections of lacquer.

Upper lacquer layers

This box was coated with a few, thickly applied lacquer layers, resulting in unstable, partially bonded films that compromised the hardening process. As these layers continued to cure, they cracked and eventually delaminated in linear patterns that ran perpendicular to the grain of the wooden core—notice the parallel rows of cracks that have developed at a 90-degree angle to the grain of the wooden core.

Powdered gold decoration

The decoration of this box was applied using traditional lacquer techniques. Gradations of gold and yellow hues were achieved with the addition of varying amounts of silver powder. Because no transparent protective finish was used to seal the decoration, however, areas of gold have worn away, exposing the red lacquer bole to which it was applied—on the lid, notice the areas of exposed dark red lacquer used to transfer and fill in the design and adhere the gold powder.