China Trade with the West

Early trade

In 1269 Venetian adventurer Marco Polo traveled to China along the Silk Road, an ancient network of overland trading trails that linked the Aegean to China, introducing the West to Chinese culture and trade goods. By the 1300s, European mariners were trading directly with India, Indonesia, and other parts of Asia. In 1553 Portuguese merchants were the first Westerners to obtain permission from Chinese officials to establish a land-based trading colony on the island of Macao, just off the coast of southern China.

East India trading companies

In 1600 and 1602 respectively, English and Dutch private investors founded East India trading companies, outfitted ships, and built trading forts throughout Asia. Chinese officials, however, restricted their access to China, allowing company agents (whom they derided as fan kwae, “foreign devils”) to trade only in securely segregated districts of a few port cities, including Canton (Guangzhou). In the 1750s, China closed all of its ports, except Canton, to Western merchants.

America and the China Trade

In 1784 American investors converted the privateer Empress of China into a merchant vessel specifically for the China Trade. Stopping at seal-fur rookeries in the South Pacific, the ship’s crew took on thousands of seal skins to sell to the Chinese—one of only a few Western commodities that Chinese merchants accepted in trade in addition to silver coin, zinc, copper, mercury, sandalwood, the dried roots of North American ginseng, and opium. Other Americans soon followed.

Opium Wars

Chinese officials banned opium in 1796 but were unable to prevent British and American smugglers from importing increasing amounts of it into the country. In 1839 Chinese troops seized a large cache of opium from Western traders, and Britain retaliated by declaring war. By 1842 the British navy had blockaded the Pearl River and the Yangtze River, forcing Chinese officials to sign the Treaty of Nanking, in which they ceded Hong Kong as a British colony and agreed to open more ports to foreign trade. Opium smuggling continued, and war broke out again in 1856. Unable to defeat British naval forces, China negotiated the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin, opening more ports to trade, legalizing opium, and ultimately contributing to the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in the early 20th century.

Canton System

First stop: Macao

Between the early 1750s and 1842, the captain of a foreign vessel seeking to trade in Canton first stopped at the Portuguese colony of Macao, at the mouth of the Pearl River. Here he received official permission to proceed up the river. Women, if on board, were required to disembark for the duration of the stay.

Second stop: Whampoa

A Chinese guide aboard a pilot boat escorted the vessel to its anchorage at Whampoa (Huang-pu), seventy miles upriver from Macao. The crew decamped, and the captain contracted with a ship supplier to provision the vessel. After receiving gifts, a “hoppo” (customs official) measured the length and breadth of the vessel to ascertain its cargo space and calculate the duty.

Final stop: Canton

Sailing in flat-bottom Chinese boats twelve miles further upriver, the captain and supercargo proceeded with the Chinese merchants and cargo to their country’s “hong” (trading house), situated on the twelve-acre plot of Canton’s waterfront walled off from the rest of the city and devoted entirely to foreign trade. Personal servants assigned to look after their needs met the men upon arrival. The supercargo selected a hong merchant (one of between eight and ten men assigned by the hoppo and approved by the emperor) to buy the inbound cargo and sell him tea, silk, porcelain, and lacquer for the outbound cargo. He also hired a translator to facilitate communication, arrange and execute payments to the customs house (closed to foreigners), oversee the transfer of purchases to the vessel at Whampoa, and attend to many other critical details of trade.

The trip home

After several months negotiating purchases and overseeing the careful packing and stowing of goods prone to spoilage and breakage on the open ocean, the captain picked up his crew on Whampoa, female passengers at Macao, and set sail for home.

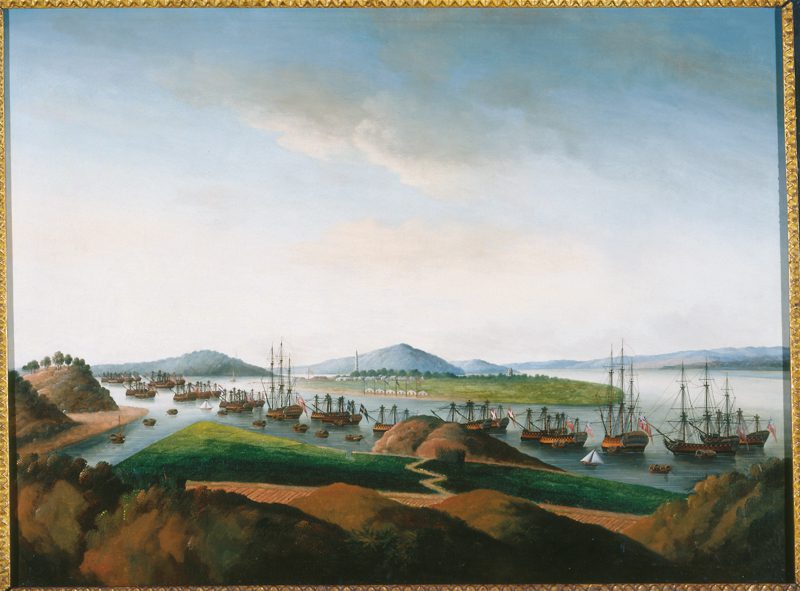

View of Whampoa Reach

China; about 1805

Oil on canvas

Gift of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.1871.003

Western merchant ships were required to anchor at the island of Whampoa, below Canton. This painting depicts 26 vessels: 13 British, 6 American, 2 Danish, 2 Swedish, 1 Dutch, 1 French, and 1 unknown. Landmarks on Whampoa Island (middle ground) included a pagoda and, on the shore, several small buildings serving Western trading partners. Here they are flying the flags of Great Britain, Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States.

This painting depicts Canton’s hongs—the name for the factories of China’s Western trading partners, which are segregated from the city. Built in rows of narrow, two-story Western-style structures facing the waterfront, each was identified by its national flag. Represented here (left to right) are Denmark, Spain, United States, Sweden, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. The waterfront is teeming with junks and flat-bottom sampans. This painting and the View of Whampoa Reach are two of four paintings of the China Trade route that Philadelphia resident John Jerome Koch brought back from China in 1819.

View of Canton

China; about 1805

Oil on canvas

Gift of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.1871.002

Miniature desk-and-bookcase

China; 1750–75

Chinese Swamp Cypress, Asian lacquer, paint, brass, iron; replaced feet

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1966.0779

Meant to amuse and delight, this miniature desk-and-bookcase served as a valuables chest, secured with locks on the full drawer, fall-front lid, and bookcase doors. A Western form, the design was possibly communicated to a Chinese artisan via a print from a European furniture design book or a drawing.

It is built in two sections: an upper “bookcase” with an enclosed bonnet with hood elements scored with saw notches to facilitate the curved shaping, and a lower “desk” set with a single full-length drawer. The upper case sits on supports within a waist molding attached to the top of the desk. The desk top forms a shallow well beneath the upper section and is lacquered and decorated with gold, suggesting that it was meant to be enjoyed as a concealed storage space between the two sections. The central section of the upper case contains a removable compartment configured as a shrine, fronted with steps and a railing and enclosed by a back painted with an image of a calligraphic hanging scroll.

The lattice diaper design in the gold decoration is similar to that of 18th-century Japanese lacquer. Europeans valued Japanese lacquer above all other Asian lacquer, but their access to examples was limited after 1639, when Japan closed its ports to all Western traders except the Dutch. To meet Western demand for lacquer in the Japanese taste, Chinese lacquer workers imitated Japanese techniques, as in this example. The piece is decorated with gold dust adhered to a wet red lacquer design imitating Japanese maki-e, which made use of gold powder. Irregular gold flakes evenly sprinkled on the interiors of the drawers mimicked Japanese nashiji—gold flake decoration.

Believed to have originated in Japan in the 11th century, the folding fan was popular in China by the 1400s. Western merchants introduced such fans to Europe in the late 1600s, and demand began to build for fans with larger leaves and ornate sticks. Chinese makers introduced examples with lacquer sticks in the mid-1700s, and by the 1820s, Chinese export lacquer fans featured brightly painted leaves depicting scenes of courtly life. This new genre is now referred to as “one hundred faces” fans, of which this fan is an example. This particular fan depicts forty-nine individuals, each with a face painted on a thin section of ivory and clothing cut from silk fabric that is glued to the paper leaf. In the 19th century, Chinese export lacquer fans were sold in matching lacquer cases that had fitted pasteboard interiors decorated with painted paper or silk.

Fan and case

Canton (Guangzhou), China; 1840–75

Paper, Asian lacquer, wood, ivory, silk, paint, gold powder

Gift of Mrs. Reginald P. Rose 1963.0018a,b