Japanned Wares: Imitation Lacquer in the West

“Japanning” is the term that describes the technique of imitating Asian lacquer with Western materials, including clear resin varnishes, paint, metallic powders, and gold leaf.

Brief history

In 1609 the Dutch East India Company secured the exclusive right to trade urushi, Japanese lacquer, at their trading house in Nagasaki, Japan. They began shipping lacquer cabinets, tables, boxes, and trays to Amsterdam, sparking a rage for what quickly became known, generically, as “japan wares.” Europeans tried, without success, to discover the secret of this lustrous material. Untrained in lacquer techniques and eager to develop methods using available materials and familiar methods, Western artisans developed the art of japanning to approximate genuine lacquer.

Japanning in England and America

In the 17th century, professional paint decorators developed japanning techniques that offered a less-expensive alternative to costly Asian lacquer wrought with gold and silver decoration on a black ground. By the 1680s, japanning had also become a fashionable pastime for middle- and upper-class young women. Targeting professionals and amateurs alike, John Stalker and George Parker were the first to publish japanning patterns and varnish recipes in their manual A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing (Oxford, 1688). Italian Jesuit missionary Filippo Buonanni first introduced European readers to the secrets of true Asian lacquer in his 1720 Treatise on Lacquer Commonly Called Chinese (Trattato Sopra la Vernice Detta Communemente Cinese).

How was japanned decoration made?

Professional japanners developed many proprietary methods and recipes. In general, the japanner required objects made from fine-grain wood. He wet the piece to raise the grain and sanded the surface smooth, repeating the process several times. Next, he sealed the base with a coat of gesso—a mixture of whiting (chalk), animal-hide glue, and a plasticizing agent such as gum arabic. He transferred the chinoiserie design, creating raised elements with gesso. After sanding the gesso ground and raised elements, he applied an undercoat of bole—red paint—followed by black.

With paint made from powdered metal (gold, silver, chemically altered silver, brass, and other metals) that was suspended in water or sizing (glue), he picked out the designs, rendering fine detail in ink or thin, black paint. The artisan sealed the completed design with coats of shellac or oil varnish, sanding each layer before applying the next. He finished the surface with a coat of beeswax cut with turpentine, buffed to a high sheen.

Tall clock

Works by Gawen Brown

Boston, Massachusetts; 1745–55

White pine, paint, gesso, gilt, brass

Museum purchase 1955.0096.003

After he finished the case for Boston clockmaker Gawen Brown (1719–1801), the cabinetmaker consigned it to a japanner for decoration. By the mid-18th century, japanners had expanded their interpretations of customary gold-on-black Asian lacquer to include new ground colors, including white, green, blue, yellow, scarlet, and tortoiseshell, as on this example.

Working on a ground of cured asphaltum, the decorator painted a design with a pigmented drying oil. Using a soft, camel-hair brush, he applied powdered gold onto the design and cleared the excess after the piece had dried. It was then sealed with tinted shellac, giving the appearance of antiqued gold leaf.

Tray

Birmingham, England; 1740–60

Sheet iron, asphaltum, gold leaf

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1967.0566

Tray

Birmingham, England, or possibly Pontypool, Usk, Wales; 1740–60

Sheet iron, asphaltum, paint, gold leaf

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1958.2282

This object was japanned with a red-pigmented oil, overlaid with asphaltum, and heat-treated to create the effect of tortoiseshell, over which powdered gold decoration was applied. Popularized in the 18th century, faux tortoiseshell grounds and blue, green, yellow, and white-hue grounds departed from the customary black of Asian lacquer, allowing japanners greater freedom in creating decorative effects. As was common in imitation lacquer produced later in the 18th century, the gold decoration on this tray combines Western imagery with Asian lacquer scenes such as isolated groupings of landscape elements and a scrolled border.

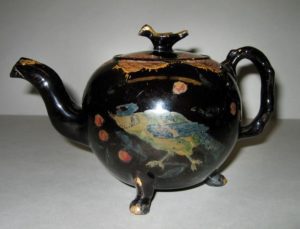

Ceramics

Staffordshire potters experimented with dark-bodied clay and lead-glaze additives such as iron filings and manganese to create products sometimes marketed as black earthenwares. Shards of black ceramics found in 18th- and early 19th-century archeological excavations in Europe and America attest to the widespread popularity of these wares. Blackwares were decorated with polychrome enamel designs, such as those that embellish this teapot, or with gold-leaf applied to raised designs, as in this tea bowl, saucer, and milk pitcher. In both instances, the applied enamel and gold-leaf decoration was “cold-painted” on top of the lead glaze and was not protected with additional glaze, which would have required another kiln firing. Prone to wear and abrasion, such decoration rarely survives.

Tea bowl and saucer

Staffordshire, England; 1750–75

Earthenware (blackware), lead glaze, gold leaf

Museum purchase 1953.0038.005a,b

Teapot

Staffordshire, England; 1750–75

Earthenware (blackware), lead glaze, enamel

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1968.0767a,b